9. State - Land and Ocean

Le rapport sur l’état de l’environnement 2022 est un document technique destiné à un usage interne. Il n’est disponible qu’en anglais.

Introduction

This focal point describes status and trends on the NWT’s coasts and ocean, including sea ice cover, ocean temperature, sea level rise, coastal erosion, and ocean acidification.

Oceans are a major component of the climate system. Changes to the ocean system can have profound effects on climate. For example, a reduction in sea ice and snow cover is accelerating climate change in the Arctic due to increased absorption of heat by darker surfaces (lowered albedo). This causes a positive feedback loop known as Arctic amplification. To understand how climate change is affecting the NWT, it is vital to understand how ocean processes are being affected.

9.1. Trends in Arctic Sea Ice and Sea Surface Temperature

This indicator provides information on observed trends and projected changes based on climate models for sea ice and surface temperature for the entire Arctic Ocean and the Beaufort Sea.

This indicator was prepared by the Government of the Northwest Territories, Department of Environment and Climate Change, using information obtained from Environment and Climate Change Canada’s Canadian Ice Service and the National Snow and Ice Data Center at the University of Colorado. Arctic sea surface temperature data for this indicator is based on various sources such as satellites, ships, buoys, and Argo floats.

NWT Focus

Changes in global climate have been observed to be and are predicted to be greater and more rapid in the Arctic than elsewhere (Ref. 1). Sea ice provides important habitat for Arctic wildlife and is an important factor affecting local and global climate. Changes in the formation of Arctic ice are affecting the NWT environment in complex ways. Sea surface temperature is intricately linked to sea ice and also affects the Arctic marine ecosystem.

Figure 1 shows the Arctic sea ice extent from 1979 to 2021, for both September (when Arctic sea ice is at its minimum) and March (when Arctic sea ice is at its maximum). As shown on the graph, Arctic sea ice extent has been steadily declining over the measured period, for both the minimum and maximum extents. September sea ice extent has been declining at a rate of 13.1% per decade (Ref. 2), and March sea ice extent has been declining at a rate of 2.6% per decade (Ref. 3).

Figure 1: September (minimum) and March (maximum) Arctic sea ice extent from 1979 to 2021. Courtesy of the National Snow & Ice Data Center, University of Colorado, Boulder (Ref. 2 and Ref. 3). Permission granted through NSIDC’s free use policy.

Current View: status and trend

Trends in sea ice in the Arctic Ocean

Figure 2 depicts images from the US National Snow and Ice Data Center, showing a comparison of the most recent minimum Arctic sea ice extent (September 2020) and the most recent maximum Arctic sea ice extent (March 2021). The magenta line represents the median ice extent between 1981 and2010.

The September 2020 (minimum) ice extent was the second lowest minimum ice extent on record, higher only than September of 2012. The total ice extent area was 3.92 million km2, just 350,000 km2 above the record low, and 2.49 million km2 less than the 1981 to 2010 average (Ref. 2).

The 2021 March (maximum) ice extent was the ninth lowest maximum ice extent on record. The total ice extent was 14.64 million km2, 350,000 km2 above the record low set in September 2017, and 790,000 km2 less than the 1981 to 2010 average (Ref. 3).

Trends in sea ice in the Beaufort Sea

The Beaufort Sea is experiencing an 8.3% decrease in summer ice extent per decade (Figure 5). While this is not the greatest ice loss in the Canadian Arctic in terms of percentage, the Beaufort Sea has experienced the greatest total ice loss of all regions since 1968, at 204,000 km2. This is equivalent to almost three times the land area of New Brunswick (Ref. 4).

September 2012 broke the 2008 record for minimum sea ice extent in the Beaufort Sea, rendering the Beaufort Sea essentially ice-free. These ice-free conditions were driven by a reduction of multi-year ice throughout previous years, ultimately resulting in thinner, more mobile single-year ice which melted more quickly. Additionally, the thinner, more mobile single-year ice could be transported out of the Beaufort Sea more easily. Melting was also enhanced by a large Arctic cyclone. Such cyclones disrupt the stratified ocean layers and allow for warmer, deeper water to reach the surface through turbulent flow, enhancing sea ice melting (Ref. 7, Ref. 8).

Trends in sea surface temperature in the Beaufort Sea

Another factor which is acting as a strong driver of reduced sea ice in the Beaufort Sea is the positive feedback of Arctic sea ice cover and ocean warming. As yearly sea ice reduces due to warming temperatures, the amount of open water increases, allowing more solar radiation to be absorbed by sea water and less to be reflected by the ice. This increased absorption warms the sea water, which promotes further melting and reduction of sea ice. This feedback is the primary driver of warming ocean temperatures in the Beaufort Sea (Ref. 9).

Arctic sea water is also warming due to large quantities of warm water entering the Arctic Ocean through the Bering Strait from the Pacific Ocean (Ref. 8). This water subducts below the cooler, less salty surface Arctic Ocean waters and extends far into the Beaufort Gyre before rising upward through turbulent mixing. This warm water is accelerating the melting of Beaufort Sea ice even further (Ref. 8).

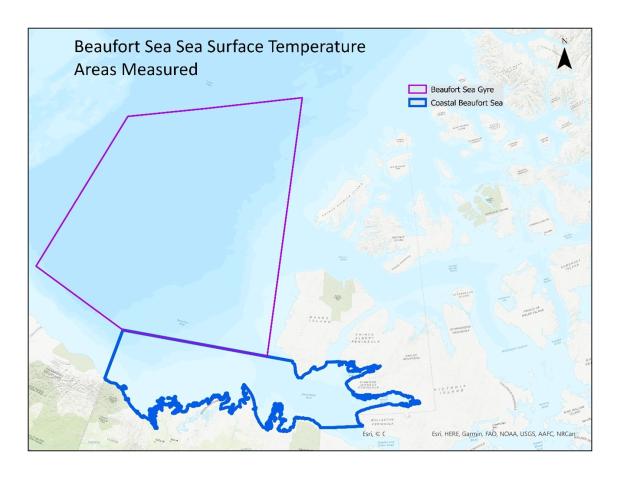

Figure 6 below shows the summer (August) mean sea surface temperature from 1982 to 2020 in the coastal Beaufort Sea and the Beaufort Gyre, as measured through a combination of various methods such as satellites, ships, buoys, and Argo floats. As seen by the trend lines, both the coastal Beaufort Sea and the Beaufort Gyre have clear warming trends, although the coastal Beaufort Sea is warming much more quickly.

Figure 7 shows the location of the Beaufort Gyre and the Coastal Beaufort Sea used for calculation of trends presented in Figure 6.

Impacts

Arctic sea ice is highly sensitive to climate change due to the sea ice-reflectivity effect. As sea ice melts and ice extent is reduced, total solar radiation absorbed by the oceans is increased because the darker ocean water absorbs more sunlight than the lighter ice. The increased solar absorption results in greater heating and in turn, a greater melting of sea ice. This positive feedback loop amplifies warming in the Arctic. Research has shown that the loss of Arctic sea ice contributes significantly to the recent amplified Arctic temperature increase compared to the global average (Ref. 4).

Sea ice is composed of ice that grows and melts each year (referred to as first-year ice) and ice that remains present all-year round (referred to as multi-year ice) (Ref. 4). Multi-year ice is thicker than first-year ice and therefore melts much more slowly. As Arctic sea ice extent is reduced more and more each year, the proportion of multi-year ice to first-year ice is becoming less and less, making it easier for more ice to melt in future years. In fact, data indicates that the vast majority of sea ice in the Arctic is new ice, with ice more than three years old primarily only found along the coastlines of Greenland and Arctic Canada, and in parts of the Beaufort Sea above Banks and Victoria Islands and Arctic Basin (Ref. 10). Thinner ice is more mobile, and its movement can be greatly influenced by storm activities and ocean currents. This can result in changing ice flow dynamics in the Arctic. For example, the vulnerability of thin ice to ocean currents was demonstrated by the dramatic and previously unobserved opening of a large flow lead in the Beaufort Sea just off the western coast of Banks Island in December 2007 - January 2008 (Ref. 11). Then again in 2013, after the record ice sheet melt of 2012, Beaufort Sea ice sheet melt rate was quicker in the earlier part of the year and the ice was more easily blown apart by windstorms (Ref. 12).

Changes in the amount, type, and location of sea ice, as well as the timing of seasonal ice formation and melt, have complex ecosystem impacts. Declining sea ice results in a loss of wildlife habitat for animals, such as polar bears, walruses, and seals. Declining sea ice also causes a decline in algae that grow on the underside of sea ice, limiting this important marine food supply (Ref. 4). Additionally, reductions in ice cover and ice thickness are resulting in increased vulnerability of Arctic coastal communities to storm surges and coastal erosion (Ref. 6) (see Indicator Sea Level Rise). Local knowledge studies indicate that changes in sea ice are resulting in increasing dangers during offshore travels, especially in fall and spring (Ref. 13, Ref. 14). Reduced sea ice and earlier break-up of sea ice (longer coastal erosion season) have resulted in more shore erosion along the Beaufort Sea coast (Ref. 15).

As Arctic sea ice melts, shipping lanes will be open longer, allowing for reduced transit times for global shipping.

Looking around

Trends in sea ice in Northern Canadian Waters

Northern Canadian Waters are composed of the Canadian Arctic domain - containing five sub-regions (Kane Basin, Foxe Basin Baffin Bay, the Beaufort Sea, and the Canadian Arctic Archipelago) - and the Hudson Bay domain, containing four sub-regions (Hudson Bay, Hudson Strait, Davis Strait, and the Northern Labrador Sea). See Figure 3 for the location of these sub-regions.

As shown in Figure 4, the area covered by summer sea ice in northern Canadian waters has been decreasing since at least 1968. Between 1968 and 2020, summer sea ice declined at a rate of 7.5% per decade. In 2020, Northern Canadian waters were covered by an average sea ice area of 1.04 million km2, representing 27.6% of the total area. The lowest summer sea ice was in 2012, with an area of 700,000 km2 (Ref. 4).

There is less decline in sea ice concentration in some areas, such as north of the Canadian Archipelago and in the Beaufort Sea west of Banks Island (Ref. 5, Ref. 6), such that the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, Beaufort Sea and Kane Basin sub-regions usually remained covered by ice in the summer because they contain a mix of seasonal and multi-year ice. This mostly occurs because ice is being piled up by the normal clockwise motion of the entire Arctic ice pack called the Beaufort Gyre. Comparatively, the four sub-regions (Hudson Bay, Hudson Strait, Davis Strait and Northern Labrador Sea) are typically free of sea ice because they are seasonal ice regions. However, all sub-regions have statistically significant decreasing ice trends between 1968 and 2018, ranging from a 3.7% decrease per decade in the Kane Basin to a 15.3% decrease per decade in the Northern Labrador Sea (Ref. 4).

In Greenland and Antarctica, sea ice exists in the form of ice shelves around the perimeter of the land mass which are fed by glaciers flowing in from the land (Ref. 19). These ice shelves occasionally calve off, creating icebergs which drift into the ocean before melting once they drift into warmer areas. Calving is a process which occurs even in the absence of climate change, but an observed increase in the rate of calving in some of the largest ice shelves in Greenland may be due to climate change. A greater indication of climate change is the disintegration of ice shelves, which is a different phenomenon than calving. Ice sheet disintegration involves a large-scale breakup of a significant portion of an ice sheet, resulting in many small ice fragments which may be swept out to sea or simply melt away over the next few decades. Such disintegration events have only been observed over the last few decades and ice core records indicate that such events may not have previously occurred anytime in the last 12,000 years. These disintegration events have caused a significant reduction in many of the ice sheets of Greenland and Antarctica. As these ice sheets retreat, they are less effective as a backstop to the land-based glaciers feeding them, resulting in a faster flow of ice from these glaciers into the sea. This accelerated movement of ice from land to sea may result in significantly increased sea levels (Ref. 16).

Looking forward

Based on satellite observations of Arctic summer ice extent since 1968, ice extent is reducing quickly, and it is likely that ice-free summers in the Arctic Ocean will soon be common. Various researchers have attempted to project the timing of the first ice-free Arctic summer year (FIASY). The FIASY is defined as the first summer in which Arctic sea ice is reduced to less than 1 million km2. The IPCC Fifth Assessment Report projects the FIASY based on an ensemble of climate models. These models provide a wide variety of projections, although most models project the FIASY to occur in the second half of the 21st century or later. However, the IPCC notes that the models appear to be underrepresenting the projected rate of ice extent loss, based on comparison with satellite records (Ref. 17). Peng et al. (Ref. 18) re-examined model projections of the FIASY and noted that models tend to interpolate linearly in their projections. They applied curve-fitting interpolation to the climate model projections and historical satellite records and found that this technique produced FIASY values in the range of 2030-2040, with a peak at 2034 (Ref. 18).

Find out more

The National Snow and Ice Data Center webpage provides daily news and analysis of the Arctic Sea Ice based on passive microwave satellite data. They provide daily mosaic satellite images of Arctic sea ice conditions: http://nsidc.org/arcticseaicenews/.

The Canadian Ice Service of Environment and Climate Change Canada is the leading authority for ice and iceberg information in Canada’s navigable waters: https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/ice-forecasts-observations/latest-conditions.html.

The Canadian Cryospheric Information Network provides a data and information management infrastructure for the Canadian cryospheric research community: https://ccin.ca.

The Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change provides more information on projections of Arctic Sea ice using climate change models. https://www.ipcc.ch/

Technical Notes

Arctic sea ice data is taken from the monthly Sea Ice Index, a collection of data and tools to examine sea ice trends and data. This data is derived from passive microwave data from the Defense Meteorological Satellite Program F-18 Special Sensor Microwave Imager/Sounder. Previous satellites and instrumentation used to collect this data include the NASA Advanced Microwave Scanning Radiometer-Earth Observing System on NASA’s Aqua satellite (of which the instrumentation is no longer functioning) and NASA’s Scanning Multichannel Microwave Radiometer satellite. Useful data collection first began in 1978 with the launch of the latter satellite.

Beaufort Sea August mean surface temperature data is derived from the Optimum Interpolation Sea Surface Temperature (OISST) provided by the NOAA. Data for the OISST is gathered through a combination of various methods such as satellites, ships, buoys, and Argo floats. This data is then applied to a global grid to provide a daily global sea surface temperature map. The methodology includes bias adjustment of satellite and ship observations to compensate for platform differences and sensor biases (Ref. 19).

The Optimum Interpolated Sea Surface Temperature (OISST) dataset is available from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

References

Ref. 1. Flato, G., Gillett, N., Arora, V., Cannon, A. and Anstey, J. 2019. Modelling Future Climate Change; Chapter 3 in Canada’s Changing Climate Report, (ed.) E. Bush and D.S. Lemmen; Government of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, p. 74–111.

Ref. 2. National Snow and Ice Data Center, October 5, 2020. “Lingering seashore days”. Available at: http://nsidc.org/arcticseaicenews/2020/10/lingering-seashore-days/.

Ref. 3. National Snow and Ice Data Center, April 6, 2021. “The dark winter ends”. Available at: https://nsidc.org/arcticseaicenews/2021/04/the-dark-winter-ends/

Ref. 4. Environment Canada. 2020. Sea Ice in Canada Canadian Environmental Sustainability Indicators. Available at: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/eccc/documents/pdf/cesindicators/sea-ice/2021/sea-ice-en.pdf.

Ref. 5. Tivy, A., S.E.L. Howell, B. Alt, S. McCourt, R. Chagnon, G. Crocker, T. Carrieres, and J.J. Yackel. 2011. Trends and variability in summer sea ice cover in the Canadian Arctic based on the Canadian Ice Service Digital Archive, 1960–2008 and 1968–2008. J. of Geophysical Research 116: C03007. 25pp.

Ref. 6. Barber, D.G., J.V. Lukovich, J. Keogak, S. Baryluk, L. Fortier, and G.H.R. Henry. 2008. The changing climate of the Arctic, Arctic: 61(1):7-26.

Ref. 7. Babb, D. G., Galley, R. J., Barber, D. G., and Rysgaard, S. 2015. Physical processes contributing to an ice free Beaufort Sea during September 2012. JGR Oceans.

Ref. 8. MacKinnon, J. A., Simmons, H. L., Hargrove, J., Thomson, J., Peacock, T., Alford, M. H., Barton, B. I., Boury, S., Brenner, S. D., Couto, N., Danielson, S. L., Fine, E. C., Graber, H. C., Guthrie, J., Hopkins, J. E., Jayne, S. R., Jeon, C., Klenz, T., Lee, C. M., Lenn, Y.-D., Lucas, A. J., Lund, B., Mahaffey, C., Norman, L., Rainville, L., Smith, M. M., Thomas, L. N., Torres-Valdés, S., and Wood, K. R. 2021. A warm jet in a cold ocean. Nature Communications.

Ref. 9. Peng, L., Zhang, X., Kim, J.-H., Cho, K.-H., Kim, B.-M., Wang, Z., and Tang, H. 2021. Role of intense Arctic storm in accelerating summer sea ice melt: an in situ observational study. Geophysical Research Letters. 48 (8). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1029/2021GL092714.

Ref. 10. AMAP. 2017. Snow, Water, Ice and Permafrost in the Arctic (SWIPA) 2017. Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP), Oslo, Norway. xiv + 269 pp.

Ref. 11. CBC. Huge fracture in Beaufort Sea ice pack worries scientists. Available at: https://www.cbc.ca/news/science/huge-fracture-in-beaufort-sea-ice-pack-worries-scientists-1.745570.

Ref. 12. CBC. NASA video captures unusual Beaufort Sea ice breakup. Available at: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/north/nasa-video-captures-unusual-beaufort-sea-ice-breakup-1.1313909.

Ref. 13. Communities of Aklavik, Inuvik Holman Island Paulatuk and Tuktoyaktuk, S. Nickels, M. Buell, C. Furgal, and H. Moquin. 2005. Unikkaaqatigiit – Putting the Human Face on Climate Change: Perspectives from the Inuvialuit Settlement Region. Ottawa: Joint publication of Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, Nasivvik. Centre for Inuit Health and Changing Environments at Université Laval and the Ajunnginiq Centre at the National Aboriginal Health Organization. Available at: http://www.itk.ca/sites/default/files/Inuvialuit.pd

Ref. 14. Pearce, T.D, B. Smit, F. Duerden, J. Ford, A. Goose, R. Inuktalik, and F. Kataoyak. 2006. Community adaptation and vulnerability to climate change in Ulukhaktok, Conference and Youth Forum 11-18 August 2006, Tuktoyaktuk, NWT.

Ref. 15. Manson G.K. and S.M. Solomon. 2007. Past and future forcing of Beaufort Sea coastal change. Atmosphere-Ocean 45:107-122.

Ref. 16. National Snow and Ice Data Center. State of the Cryosphere: Ice Shelves. Last updated June 22, 2019. Available at: https://nsidc.org/cryosphere/sotc/iceshelves.html

Ref. 17. Meredith, M., M. Sommerkorn, S. Cassotta, C. Derksen, A. Ekaykin, A. Hollowed, G. Kofinas, A. Mackintosh, J. Melbourne-Thomas, M.M.C. Muelbert, G. Ottersen, H. Pritchard, and E.A.G. Schuur. 2019: Polar Regions. In: IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, M. Tignor, E. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Nicolai, A. Okem, J. Petzold, B. Rama, N.M. Weyer (eds.)]. In press.

Ref. 18. Peng, G., Matthews, J. L., Wang, M., Vose, R., and Sun, L. 2020. What do global climate models tell us about future Arctic sea ice coverage changes? Climate, 8(1), 15; https://doi.org/10.3390/cli8010015.

Ref. 19. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Optimum Interpolation Sea Surface Temperature (OISST). Accessed May 15, 2021. Available at: https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/oisst

9.2. Trends in ocean acidification in the Beaufort Sea

This indicator reports on trends in observed Arctic ocean acidification, primarily in the Beaufort Sea, and projected changes based on climate models.

This indicator was prepared by the Government of the Northwest Territories, Department of Environment and Climate Change, using information obtained from published documents mostly based on ocean observations conducted through many scientific expeditions conducted by National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

NWT Focus

Ocean acidification is predicted to increase more rapidly in the Arctic, particularly the Beaufort Sea, than anywhere else globally. Ocean acidification levels are a crucial component of the marine ecosystem, and increased levels have already had an impact on marine organisms.

Current View: status and trend

As CO2 levels in the atmosphere continue to rise, much of this CO2 is absorbed by the ocean, increasing acidification and reducing pH. Globally, this process has caused the ocean to become 30% more acidic on average (Ref. 1). However, acidification levels in the Arctic have been increasing at a greater rate than the global average because cold water can absorb more CO2 than warm water (Ref. 2). Additionally, enhanced sea ice melt, respiration of organic matter, upwelling, and riverine inputs have all been shown to enhance ocean acidification in high latitude regions, particularly in the Pacific-Arctic region near the Beaufort Sea (Ref. 1). As sea ice continues to shrink due to a warming climate, the increased exposure of open ocean to the atmosphere will accelerate the rate of ocean acidification in the Arctic. Due to its extremely high susceptibility to ocean acidification, the Pacific-Arctic region has been termed the “canary in the coalmine” for the rest of the global ocean (Ref. 1).

Within the Beaufort Sea, an undersaturation of aragonite was first reported in 2009 (Ref. 2). Aragonite is a type of calcium carbonate which acts as a primary building block of shells for marine organisms. An undersaturation of this mineral in seawater means that for the first time, the ocean in this region was actually corrosive to the shells of these organisms. Researchers in 2020 (Ref. 3) reported a more in-depth examination of ocean acidification in the Beaufort Sea with observations conducted from 1997 to 2016. They measured the saturation state of seawater, recording how undersaturated or oversaturated seawater is with respect to aragonite. An undersaturation means that aragonite tends to dissolve in seawater, and thus the seawater is corrosive to shelled organisms. The results showed that the saturation state of seawater decreased rapidly between 2003-2007, at a rate ten times greater than in the open ocean. This was caused by the melting and retreat of sea ice, which diluted sea water and caused a ‘dilution effect’, lowering the concentration of Ca2+in the ocean, resulting in a lowered aragonite saturation state. Additionally, the retreat of sea ice increased the size of the open ocean, allowing for greater air-sea CO2 exchange. This rapid decline resulted in an undersaturation of aragonite in the ocean. After 2007, the saturation state increased slightly and stabilized. It has remained primarily in an undersaturated state since 2007 (Ref. 3). The saturation state recorded from 1997 to 2016 in the Beaufort Sea is shown in Figure 1.

The effect of increased ocean acidification is an increase in corrosion to shelled marine animals, including plankton and other invertebrates. If the acidification becomes too great, it will impact the ability of these organisms to survive in these regions of the ocean. Already, research has shown that up to 70% of pteropod shells in the Beaufort Sea have corroded shells. Pteropods are tiny sea snails which represent an abundant and critical food source for Arctic food webs, often dominating zooplankton communities and feeding animals ranging from pink salmon to whales (Ref. 5). Their abundance is critical to the health of these Arctic food webs, including traditional country food sources for Indigenous populations. Given the concerning results of existing studies of ocean acidification and its results on marine organisms in the Beaufort Sea, more research of this phenomenon and its effects in the Beaufort Sea is warranted.

Looking forward

In its Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change provides generalized global ocean acidification projections which suggests a decline in pH of 0.042 by 2081 to2100 under Representative Concentration Pathway 8.5 (high emissions scenario). They also state that the greatest changes will occur in the Arctic Ocean (Ref. 4).

For a closer look at the Beaufort Sea specifically, researchers projected ocean acidification in the Beaufort Sea, Bering Sea, and Chukchi Sea, using model-based outputs from the Community Earth System Model and direct ocean observations in 2011 and 2012 (Ref. 1). Results indicate that the Beaufort Sea is the most strongly affected by ocean acidification. In fact, the average annual saturation state for this sea is already below 1 (undersaturated) with respect to aragonite, and has been since 2001. The saturation state is projected to continue to decrease, reaching just above 0.4 by 2100 (Ref. 1). Figure 2 shows the model output of projected saturation state for this study.

This same study took an additional step to identify the years in which the saturation state was likely to go below the threshold for which marine life could cope. This was done by presuming that a saturation state below natural variability would be the point at which there would be impacts to marine life. Using this assumption and comparing the natural variability in saturation state with their model projections, they estimate that in the Beaufort Sea there may be impacts by 2025 (Ref. 1). Such a short timeline strongly highlights the immediacy of the ocean acidification issue in the Beaufort Sea.

Find out More

More information on Arctic acidification can be found in in Arctic Acidification Assessment: 2018 Summary for Policymakers report by AMAP. Available at: https://www.amap.no/documents/download/3296/inline

Other indicators that focus on the Beaufort Sea are:

- Indicator 9.1: Trends in temperatures in the Beaufort Sea

- Indicator 9.3: Trends in projected sea rise levels in Beaufort Sea

References

Ref. 1. Mathis, J. T., J. N. Cross, W. Evans, and S. C. Doney. 2015. Ocean acidification in the surface waters of the Pacific-Arctic boundary regions. Oceanography 23(2):122-135. Available at: https://doi.org/10.5670/oceanog.2015.36.

Ref. 2. Yamamoto-Kawai, M., McLaughlin, F. A., Carmack, E. C., Nishino, S., and Shimada, K. 2009. Aragonite Unersaturation in the Arctic Ocean: Effects of Ocean Acidification and Sea Ice Melt. Science, v. 326: pp. 1098-1100.

Ref. 3. Zhang, Y., Yamamoto-Kawai, M., and Williams, W. J. 2020. Two decades of ocean acidification in the surface waters of the Beaufort Gyre, Arctic Ocean: effects of sea ice melt and retreat from 1997-2016. Geophysical Research Letters, v. 47(3).

Ref. 4. Bindoff, N.L., W.W.L. Cheung, J.G. Kairo, J. Arístegui, V.A. Guinder, R. Hallberg, N. Hilmi, N. Jiao, M.S. Karim, L. Levin, S. O’Donoghue, S.R. Purca Cuicapusa, B. Rinkevich, T. Suga, A. Tagliabue, and P. Williamson. 2019: Changing Ocean, Marine Ecosystems, and Dependent Communities. In: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, M. Tignor, E. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Nicolai, A. Okem, J. Petzold, B. Rama, N.M. Weyer (eds.)]. In press.

Ref. 5. McKittrick, E. 2019. The shells of wild sea butterflies are already dissolving. Hakai Magazine. Available at: https://www.hakaimagazine.com/news/the-shells-of-wild-sea-butterflies-are-already-dissolving/.

9.3. Trends in Projected Sea Level in the Beaufort Sea

This indicator reports on sea-level projections at coastal communities and regions around the Beaufort Sea in the Northwest Territories.

Sea-level projections are estimated in Arctic regions by combining data on global sea level changing due to glacial melting from a warming climate, thermal expansion of sea water, post-glacial rebound (“vertical land motion”), and sea-level fingerprinting (the gravitational effect of glaciers, ice caps and ice sheets). These terms are further explained below.

This indicator was prepared by the Government of the Northwest Territories, Department of Environment and Climate Change, using information obtained from various sources. Sea-level projections for NWT communities along the Beaufort Sea were estimated for this indicator by the Geological Survey of Canada, Natural Resources Canada (NRCan) based on sea level projections from the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, and additional methods to account for vertical land motion sea level fingerprinting, as described in James et al. (Ref. 1).

NWT Focus

Increases in sea level are partly responsible for the observed and projected changes on the Mackenzie Delta ecosystem and other coastal areas in the NWT, such as the observed effects of a storm surge on the Mackenzie Delta in 1999 (discussed in more detail in the Looking Forward section below). Projected sea-level changes in the Beaufort Sea are an important component of future changes to NWT coasts, and have the potential to affect infrastructure, ecosystems, and biodiversity.

Current View: status and trend

Global sea levels

Global mean sea level has been rising as global temperatures increase. This is due to meltwater from glaciers and ice sheets, as well as from the thermal expansion of sea water as it becomes warmer. Until recently, meltwater and thermal expansion have contributed a roughly equal amount to rising sea levels. However, rising temperatures have caused the rate of glacial melting to dramatically increase. Since 1880, global mean sea level has increased between 21-24 centimeters, but the rate of increase has accelerated from 1.4 millimeters per year through most of the 20th century, to 3.6 millimeters per year between 2006 and2015. Melting glaciers now account for nearly twice the amount of sea level rise as thermal expansion (Figure 1, Ref. 2).

For an NWT perspective on current observed sea levels, the community of Tuktoyaktuk is a good case study since the community is under threat due to rising sea levels and coastal erosion. Figure 2 shows sea levels in Tuktoyaktuk based on records going back to 1961. Despite a 25-year gap in the data, there is a clear rising trend in sea level of 2.75 millimeters per year at Tuktoyaktuk. The community is currently experiencing the consequences of these rising seas, as they are at least partially responsible for the necessary relocation efforts of buildings along the coast of the community.

In the 2019 Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate (Ref. 4), the IPCC estimated that by 2100, global mean sea level (GMSL) will rise between 0.29 and0.59 m in a low emissions scenario (RCP 2.6) and between 0.61 and1.10 m in a high emissions scenario (RCP 8.5). The possibility of a GMSL rise greater than 1 meter is supported by other researchers (Ref. 5, Ref. 6, Ref. 7). Sea-level rise greater than two meters by the year 2100 appears to be a very low probability (Ref. 8).

Vertical land motion

Locally, the amount of sea-level change is affected by two additional factors. First, vertical land motion affects the amount of sea-level change that is experienced locally. If the land is sinking, sea-level rise will be increased locally, and if the land is rising, sea-level rise will be decreased locally. In the Canadian Arctic, vertical land motion is occurring primarily due to a process known as isostatic adjustment. This process is caused by recovery from a thick ice sheet which was centered over the Hudson Bay region during the last glaciation. The sheer weight of this ice sheet caused the ground beneath to be pushed down, much like pushing a dent into a ping pong ball. Deep within the Earth, this weight from above pushed the mantle horizontally away from the ice sheet, resulting in the area around the periphery of the ice sheet to be pushed up. Once the ice sheet melted at the end of the glaciation, all of the weight was lifted, and the ground was able to move back into its original position. However, this vertical ground movement occurred very slowly, at a rate of a few centimeters per year maximum, and in fact is still occurring today. Nearer to Hudson Bay where the ground was pushed down, it is slowly moving back up, and along the edge of the former ice sheet, it is slowly moving back down.

Unlike some parts of Nunavut, such as western Hudson Bay, where the land is rising quite rapidly at nearly one centimeter per year, coastal communities in the NWT are rising much more slowly as they are located near the periphery of the former ice sheet. Vertical land motion ranges from uplift of about 3.11 ±0.56 mm/year at Ulukhaktok, to 0.99 ±0.87 mm/year at Sachs Harbour, to subsidence or sinking 1.04 ±0.55 mm/year at Tuktoyaktuk (Ref. 1). Hence for Tuktoyaktuk, not only is the sea rising, but the ground is sinking. This subsidence is the result of Tuktoyaktuk being located at the periphery of the former ice sheet, where the ground was lifted. The ground here is now sinking to return to its original position. This is an estimate of the vertical motion of bedrock and does not take into account subsidence due to compaction or thawing permafrost, nor does it take into account possible vertical motion due to tectonic activity. Continued and new monitoring with Global Positioning System (GPS) installations provide direct observations of vertical crustal motion at sites of interest.

Sea-level fingerprinting

Sea level fingerprints are the patterns of local sea level rise that occur as ice caps, ice sheets, and glaciers melt into the ocean. As a glacier melts it loses mass and its gravitational attraction is reduced. Ocean waters nearby move away, causing sea levels to rise faster away from the glacier. While melting glaciers will still cause an increase in the global average sea-level, the sea level in the nearby surrounding waters of the glacier will be lower due to the sea level fingerprinting. Figure 3 shows the effect of sea-level fingerprinting on sea-level globally (in isolation of all other factors) from a) Antarctica, b) Greenland, and c) mountain glaciers and ice caps.

As can be seen in Figure 3(b), the effect of sea-level fingerprinting from Greenland on the Arctic is substantial. The melting of the Greenland glacier is causing a fall in relative sea levels due to sea-level fingerprinting across Arctic Canada, and especially nearer to Greenland. Additionally, as seen in Figure 3(c), sea-level fingerprinting is also causing a fall in sea-levels in the western Canadian Arctic due to melting mountain glaciers and ice fields of the Coast Mountains and the Gulf of Alaska (Ref. 10). It should be noted that while sea-level fingerprinting is causing a fall in sea-level, other factors such as rising global sea levels due to melting of other, more distant glaciers, is causing overall sea-levels in many parts of the Arctic to still be rising. This is particularly true for areas in the western Canadian Arctic which are more distant from Greenland than areas further east.

Thomas James (NRCan, personal communication) illustrated the importance of sea-level fingerprinting in the Canadian Arctic by providing some specific values of sea-level change that this effect causes in specific Arctic communities. Currently glaciers in Greenland are massive and gravitationally pull sea water towards Greenland, resulting in an increased local sea level. Conversely, if the melting glaciers in Greenland are contributing one millimeter per year to global sea-level rise, near Greenland sea level will fall by 1.2 mm / year at Iqaluit as the Greenland glaciers have diminished and are pulling the sea water less towards Greenland. Further away, this gravitational effect is smaller. Due to this effect, in coastal communities in the NWT the local sea level rise ranges from +0.2 mm/yr (Tuktoyaktuk) to -0.1 mm/year (Ulukhaktok) for a 1 mm/year Greenland contribution to global sea-level rise. Paulatuk and Sachs Harbour have intermediate values (T. James, personal communication). Because the Greenland ice sheet is an important contributor to global sea-level rise projections, sea-level fingerprinting reduces projections of local sea-level rise in the Canadian Arctic.

Overall projected sea-level for NWT communities and areas along the coast

James et al. (Ref. 11) developed projections of sea-level change nationally and regionally across Canada, for 2006 and for every decade from 2010 to 2100. Their projections are based on IPCC Fifth Assessment Report projections, with updates for vertical land motion based on a crustal velocity model developed using GPS velocity measurements at specific locations. Sea-level fingerprinting was also included in the projections. Maps of sea level projections across the coastal regions of Canada were developed at 0.1° in latitude and longitude. Figure 4 shows the median relative sea-level change projection for 2050 for the high emissions scenario (RCP 8.5), for the north coast of Canada.

Figure 5 shows sea-level projections for four NWT coastal communities and two coastal regions for 2100 under a high emissions (RCP 8.5) climate scenario. The median (middle of the distribution of all the projection data) and 95th percentile projections (point in the distribution of all the projection data where 95% of the data is below) are shown in the graph. The projections show that all four communities are expected to experience sea-level rise in the 21st century. At the upper end of the projections (95th percentile), Tuktoyaktuk, Baillie Island, and Cape Bathurst may experience over 1 m of sea-level rise. On the other end of the projections, Paulatuk has a median projected sea level rise of less than 20 cm and 95th percentile projected sea level rise of no greater than approximately 40 cm of sea-level rise for 2100 (Figure 5).

Figure 6 shows a time series of projected sea-level rise, inclusive of vertical land motion and fingerprinting, for the same NWT communities and areas included in Figures 4 and 5. The graph shows projections for three emissions scenarios (low, medium and high; RCP2.6, RCP4.5, RCP8.5), and an enhanced scenario in which a portion of the western Antarctic ice sheet collapses leading to an extra 65 cm in sea level rise worldwide (RCP 8.5 enhanced) (Ref. 11). Compared to the median projection, there is a lower probability of the 95 percentile sea level rise and the Antarctic ice sheet collapse scenario. James et al. (Ref. 11) notes that a sea level rise greater than the Antarctic ice sheet collapse scenario is possible but has a low probability. For construction of high value infrastructure (e.g. health facilities), where there is a low tolerance for sea level rise it is recommended to consider higher scenarios of global sea level rise so that there is lower probability of such infrastructure being inundated [1].

[1] For coastal planning and coastal infrastructure design it is recommended to seek guidance on the most current sea level rise projections from ECC or NRCan.

The projections presented here are for the change in mean sea level. For the permafrost-rich sediments that comprise much of the Beaufort coastline of the NWT, changes in the frequency and intensity of storms, sea ice, wave energy, and water and air temperatures, among other factors, will also impact coastal erosion, in addition to rises in sea level. These factors are not considered here. The sea level rise projections are based on current information. It is anticipated that advances in the understanding of projected global sea levels and in the understanding and observation of local effects, such as vertical land motion, will lead to future revisions in projected sea levels.

Looking around

Iqaluit is projected to experience a sea level rise of up to 31.8 cm by 2100 (Ref. 1). Not all Arctic coastal areas have projected sea level rise. Sea levels could decrease in eastern portions of Nunavut – by as much as 105.6 cm at Igloolik by 2100 (Ref. 1). Sea level decreases in Nunavut may impede marine transportation.

Taking into account vertical land motion and sea-level fingerprinting, as described above, the assessment of the likely amount of global sea-level change ranges from 26 cm to 98 cm to the year 2100 (a range of 72 cm) (Ref. 1).

Looking forward

For the Beaufort Sea coast, all projections suggest an increase in sea level at most NWT communities over the next 100 years. The issue is exacerbated in many areas of the Beaufort Sea coastline, where unconsolidated sediment is held together by permafrost, allowing for quick erosion as permafrost thaws from the thermal impact of ocean water and warming ambient temperatures due to climate change (Ref. 10, Ref. 13). This accelerated coastal erosion is having a major impact on the traditional lifestyles of the local Inuvialuit residents. For example, the community of Tuktoyaktuk is experiencing extreme coastal erosion which is endangering the homes of those living along the coast. Homes may need to be relocated. This erosion is also impacting local ecosystems. The Hairy Braya, Braya Pilosa, (Figure 7) an Arctic flower which only grows on the cliffs of Cape Bathurst and adjacent Baillie Island (Figure 8), is threatened as Cape Bathurst quickly erodes into the sea (Ref. 14). The Hairy Braya is the first NWT threatened species with a recovery strategy that addresses climate change (Ref. 15).

Additionally, it is predicted that sea level rise, in conjunction with reduced sea ice, will result in more frequent and more extreme storm surges (Ref. 16). The Beaufort Sea is already susceptible to storm surges due to its shallow shelf bathymetry (Ref. 10), and these changes will only increase its vulnerability. In 1999, an exceptionally high storm surge moved salt water far above the normal surge lines of the Mackenzie Delta, transforming the outer delta ecosystem, killing shrubs and changing the ecology of some delta lakes from freshwater systems to brackish ones (Ref. 17). Evidence from traditional knowledge, shrub growth (dendrochronology) and lake diatoms show that this type of large scale storm surge had not occurred in the Mackenzie Delta in the past 1,000 years. This type of event may become the new norm (Ref. 17). Using modelling, Kim et al. (Ref. 18) found that storm surges in the Beaufort Sea under ice free conditions may be up to three times higher than under present day ice conditions. Hence in the future, storm surges will be more significant along Canada’s Arctic coast, magnifying the impact of rising sea levels.

Find out more

For more information on global climate change go to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change at https://www.ipcc.ch/.

For more information on changes to Canada’s coastlines, see the Government of Canada’s report on Canada’s Marine Coasts in a Changing Climate at https://www.nrcan.gc.ca/sites/www.nrcan.gc.ca/files/earthsciences/pdf/assess/2016/Coastal_Assessment_FullReport.pdf.

References

Ref. 1. James, T.S., Henton, J.A., Leonard, L.J., Darlington, A., Forbes, D.L., and Craymer, M. 2014. Relative Sea-level Projections in Canada and the Adjacent Mainland United States; Geological Survey of Canada, Open File 7737, 72 p. doi:10.4095/295574.

Ref. 2. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2021. Climate Change: Global Sea Level. Available at: https://www.climate.gov/news-features/understanding-climate/climate-change-global-sea-level

Ref. 3. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration – Tides and Currents. Relative Sea Level Trend 970-211 Tuktoyaktuk, Canada. Available at: https://tidesandcurrents.noaa.gov/sltrends/sltrends_station.shtml?id=970-211.

Ref. 4. Oppenheimer, M., B.C. Glavovic , J. Hinkel, R. van de Wal, A.K. Magnan, A. Abd-Elgawad, R. Cai, M. Cifuentes-Jara, R.M. DeConto, T. Ghosh, J. Hay, F. Isla, B. Marzeion, B. Meyssignac, and Z. Sebesvari. 2019: Sea Level Rise and Implications for Low-Lying Islands, Coasts and Communities. In: IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, M. Tignor, E. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Nicolai, A. Okem, J. Petzold, B. Rama, N.M. Weyer (eds.)]. In press.

Ref. 5. Grinsted, A., J.C. Moore, and S. Jevrejeva. 2009. Reconstructing sea level from paleo and projected temperatures 200 to 2100 AD. Climate Dynamics, 34, 461-472.

Ref. 6. Rahmstorf, S. 2007. A semi-empirical approach to projecting future sea-level rise. Science 315: 368-370.

Ref. 7. Vermeer, M. and S. Rahmstorf. 2009. Global sea level linked to global temperature. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106: 21527-21532.

Ref. 8. Pfeffer, W.T., J.T. Harper, and S. O’Neel. 2008. Kinematic constraints on glacier contributions to 21st-century sea-level rise. Science 321: 1340-1343.

Ref. 9. Mitrovica, J.X., Tamisiea, M.E., Davis, J.L., and Milne, G.A. 2001. Recent mass balance of polar ice sheets inferred from patterns of global sea-level change. Nature, v. 409, pp. 1026-1029.

Ref. 10. Lemmen, D.S., Warren, F.J., James, T.S. and Mercer Clarke, C.S.L. editors. 2016. Canada’s Marine Coasts in a Changing Climate; Government of Canada, Ottawa, ON, 274p.

Ref. 11. James, T.S., Robin, C., Henton, J.A., and Craymer, M. 2021. Relative sea-level projections for Canada based on the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report and the NAD83v70VG national crustal velocity model; Geological Survey of Canada, Open File 8764, 1 .zip file, https://doi.org/10.4095/327878.

Ref. 12. Dyke, A.S., Moore, A. And Roberson, L. 2003. Deglaciation of North America, Geological Survey of Canada Open File 1574.

Ref. 13. Obu, J., H. Lantuit, G. Grosse, F. Günther, T. Sachs, V. Helm, M. Fritz. 2016. Coastal erosion and mass wasting along the Canadian Beaufort Sea based on annual airborne LiDAR elevation data, Geomorphology. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2016.02.014.

Ref. 14. Harris, J. G. 2013. Assessment and Status Report on the Hairy Braya (Braya pilosa) in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Available at: https://www.registrelep-sararegistry.gc.ca/virtual_sara/files/cosewic/sr_hairy_braya_poilu_1213_e.pdf

Ref. 15. Government of the Northwest Territories Department of Environment and Climate Change. 2015. Recovery Strategy for the Hairy Braya (Braya pilosa) in the Northwest Territories. Yellowknife. 30 pp. https://www.nwtspeciesatrisk.ca/sites/enr-species-at-risk/files/hairy_braya_recovery_strategy_approved_nov915_w_properties_0.pdf.

Ref. 16. Manson, G.K., and S.M. Solomon. 2007. Past and future forcing of Beaufort Sea coastal change, Atmosphere-Ocean, 45:2, 107-122, DOI: 10.3137/ao.450204.

Ref. 17. Pisaric, M.F.J., Thienpont, J.R.., Kokelj, S.V., Nesbitt, H., Lantz, T.C., Solomon, S., and Smol, J.P. 2011. Impacts of a recent storm surge on an Arctic delta ecosystem examined in the context of the last millennium. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108:8960-8965.

Ref. 18. Kim, J.,E. Murphy, I. Nistor, S. Ferguson, M. Provan. 2021. Numerical Analysis of Storm Surges on Canada’s Western Arctic Coastline J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 9, no. 3: 326. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse9030326.