17. Stewardship - Planning and Adapting

Le rapport sur l’état de l’environnement 2022 est un document technique destiné à un usage interne. Il n’est disponible qu’en anglais.

Introduction

This final section identifies stewardship actions that may reduce the impact of driving forces and pressures and improve or maintain the state of our environment.

Planning and adapting our actions are important first steps in effective stewardship programs. In this focal point, we track how our planning and adaptation efforts are implemented, through our Transboundary Water Agreements, Water Stewardship Strategy and Action Plan, Species at Risk Recovery Strategies and Climate Change Strategic Framework and Action Plan. Additional planning and adaptation programs will be tracked in future report, if applicable.

17.1. Status of Transboundary Water Agreements

In 1997, the jurisdictions of British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, the Yukon Territory, the Government of the Northwest Territories (GNWT) and Government of Canada signed the Mackenzie River Basin Transboundary Waters Master Agreement (Master Agreement) which committed each part to collaborate together to maintain the ecological integrity of the entire Mackenzie River Basin and to negotiate Bilateral Water Management Agreements (Bilateral Agreements). The Northwest Territories (NWT) is the downstream jurisdiction in the Mackenzie River Basin and as such is impacted by upstream management decisions. However, the NWT plays a key role to ensure upstream water protection in water basins that are shared with Nunavut.

The negotiation and implementation of the NWT’s Bilateral Agreements is important to ensure we can achieve the vision of Northern Voices, Northern Waters: NWT Water Stewardship Strategy and that the waters of the NWT remain clean, abundant and productive for all time. Bilateral Agreements are an important way to protect waters flowing across boundaries and establish common understanding and expectations for those sharing that water. Effectiveness of these agreements can be determined by assessing how information is being shared and the state and trend of water, including quantity, quality and biology, flowing into the NWT.

This indicator provides information on the status of negotiation and implementation of the NWT bilateral agreements with neighbouring jurisdictions.

This indicator was prepared by the Government of the Northwest Territories, Department of Environment and Climate Change using internal information.

NWT Focus

The GNWT is implementing agreements with Alberta, British Columbia and the Yukon. The Yukon-NWT Bilateral Agreement, originally signed in 2002, has involved regular meetings and ongoing water quality and quantity monitoring of the Peel River. It is currently being updated to align with the newer Bilateral Agreements. The GNWT is currently negotiating a similar agreement with Saskatchewan. The GNWT has reached out to Nunavut to begin negotiations but formal negotiations have not yet begun. These Bilateral Agreements create a framework for cooperation and informed decision making with the objective to maintain the health of the aquatic ecosystem, which includes water quality, water quantity, groundwater, and aquatic life (the biological component).

The Bilateral Agreements commit jurisdictions to share information about current and proposed developments and consult each other if there are concerns. The Bilateral Agreement with Alberta, for instance, sets out triggers which are designed to identify potential changes in water quality and quantity. Further, the Alberta-NWT Bilateral Agreement has established monitoring plans for aquatic insects and fish so that biological indicators can be used to assess ecosystem health. Management actions are set based on risk, and jurisdictions are obliged to take specific actions to meet the goal of protecting ecosystem health. Water quality, quantity, and biological indicators are monitored near the border and information from regional and basin level monitoring is regularly assessed.

The Bilateral Agreements contain a commitment to annually report on implementation progress, including monitoring activities and results. Together, the jurisdictions review and analyze the monitoring data frequently and discuss the results together. Under the Alberta-NWT Bilateral Agreement, we have released four annual reports since signing the agreement (for years 2015-16, 2016-17, 2017-18, and 2018-2020). Annual reports are available to the public on the ECC website at https://www.ecc.gov.nt.ca/en/services/water-management-and-monitoring/alberta-nwt-transboundary-water-agreement.

The NWT actively monitors conditions on key rivers that cross our borders to assess conditions and ensure BWMA commitments are being maintained. As the downstream jurisdiction, upstream activities (e.g., the Oil Sands (Alberta) and Bennett Dam (British Columbia) have the potential to impact water quality, quantity and biology in the NWT. Under each Bilateral Agreement, a Bilateral Management Committee (BMC) is established to bring forward input and interests from the public and Indigenous governments and Indigenous organizations, to facilitate joint implementation and to provide a forum for collaboration. Each BMC includes an Indigenous Member from each jurisdiction to ensure Indigenous interests are represented in BMC decision making. In the NWT, the Indigenous Member is nominated by the Indigenous Steering Committee which was established to guide the development and implementation of water stewardship activities as part of Northern Voices, Northern Waters: NWT Water Stewardship Strategy. The Indigenous Steering Committee also nominates the NWT Indigenous member to the Mackenzie River Basin Board.

The Mackenzie River Basin Board was established by Master Agreement in 1997. The Board provides a forum for collaboration across the Mackenzie River Basin and has members from each of the provincial, territorial and federal governments as well as Indigenous members from each of the provinces and territories. A Traditional Knowledge and Strengthening Partnership Committee, a Science Committee, and specific task teams support the work of the Board. These committees are able to tackle basin-wide topics (such as developing consensus-based approaches to water quality data analysis and objective setting) that help implement the Bilateral Agreements in the basin.

Current View: status and trend

Bilateral Agreements contain a series of management actions for shared waters, including monitoring, learning plans and setting transboundary water objectives. For example, the Alberta-NWT Bilateral Agreement has established a series of triggers to assess transboundary waters and proactively address negative trends in water quality and quantity for the Slave and Hay rivers. These triggers are set at a level to provide an early warning system of change. Alberta and the NWT use data from upstream sites in Northern Alberta to help explain downstream conditions at the border.

Bilateral Agreements use a risk informed management approach to classify shared waters. Depending on the level of risk, traditional use, cultural importance and concern about upstream development, the shared waterways can be classified as 1, 2, 3 or 4. Class 1 waters only require the level of monitoring already being undertaken. Class 2 water bodies require Learning Plans to better understand the history, current and potential future of water quality, quantity and health of the overall aquatic ecosystem. Class 3 water bodies are considered at a higher risk and interest and support greater traditional use. In addition to Learning Plans, Class 3 waters require the development and monitoring of site-specific objectives. Class 4 is only assigned if objectives for a body of water are not being met, and corrective action is immediately needed.

The Alberta-NWT Bilateral Agreement is the only agreement with class 3 water bodies – the Slave and Hay rivers – and therefore requires triggers and objectives be set, Under the British Columbia-NWT Bilateral Agreement, the Liard and Petitot rivers are class 2 for surface and groundwater quality and therefore could have triggers and do require learning plans which are currently under development.

All Mackenzie River Basin Bilateral Agreements are designed to maintain the ecological integrity of the aquatic ecosystem so that all uses, including traditional use, are protected. Indigenous and local knowledge as well as science are all used to support decision-making on transboundary waters. Results of monitoring and implementation activities are reported publicly through annual reports. For example, as part of these annual reports, current conditions on the Slave and Hay rivers are compared to values that have been calculated from historical data. These triggers are called site-specific water quality triggers because they reflect the site-specific conditions of each river. Comparing the data to these triggers indicates if levels of a particular substance are changing or if levels are higher than what is expected.

An example of one result included in annual reports is that concentrations of dissolved magnesium [1] in the Slave River, have exceeded the trigger since 2015, exhibiting an increasing trend over time (Figure 1; p<0.0001; n=274). Why? To answer this question, we can look at data from upstream monitoring sites on the Peace and Athabasca Rivers. A similar trend was found for dissolved magnesium in the Peace River, but not in the Athabasca. Given that the Peace River contributes almost 80% of the water to the Slave River, it is likely that the changes in the Slave River are being driven by changes in the Peace River. In 2022, we plan to investigate the reasons for this change in the Peace River by assessing local land use changes and potential climate change signals in the region.

[1] Magnesium is a natural constituent of surface water. The concentration of magnesium in water can be affected by natural processes, like runoff or increased weathering of rock, and by human activity, like land clearing.

Transboundary agreements are proving to be effective tools to address transboundary concerns related to water management.

Looking around

Unlike transboundary agreements in other parts of Canada, which only focus on water quality or apportioning water, the Mackenzie River Basin transboundary water management agreements include both, as well as overall aquatic health. The agreements are inclusive of Indigenous knowledge, monitor the biology of shared waters, and surface water and groundwater quality and quantity. Commitments in the agreements include monitoring, creating learning plans and setting triggers and objectives, making the agreements one of the most comprehensive of their kind.

Looking forward

Transboundary water agreements are important for assessing and protecting the waters flowing into and out of the NWT. The GNWT will continue advancing negotiations to complete transboundary agreements with its neighbours, including Saskatchewan and Nunavut. As well, the GNWT will continue working with its neighbours to implement existing agreements.

Find out more

For more information about the Mackenzie River Basin Transboundary Waters Master Agreement visit the Mackenzie River Basin Board website:

https://www.mrbb.ca/?msclkid=e70606bace7911ecb703d34092e3adb3

For more information on the transboundary agreement with Alberta visit: https://www.ecc.gov.nt.ca/en/services/water-management-and-monitoring/alberta-nwt-transboundary-water-agreement.

For more information on the transboundary agreement with British Columbia visit: https://www.ecc.gov.nt.ca/en/services/water-management-and-monitoring/bc-nwt-transboundary-water-agreement.

Technical reports to support transboundary agreement implementation are available to the public on the ECC website at https://www.ecc.gov.nt.ca/en/services/water-management-and-monitoring/transboundary-water-agreement-implementation.

17.2 Status of Implementation of the Water Stewardship Strategy

This indicator provides information about the implementation status of Northern Voices, Northern Waters: NWT Water Stewardship Strategy (Water Strategy) (Ref. 1). The Water Strategy is a made-in-the-North strategy developed collaboratively by water partners in the NWT.

Since the Water Strategy was first released in 2010, water partners have developed three five-year Action Plans (2011-2015, 2016-2020, and 2021-2025) (Ref. 2, 3, 4).

The Water Strategy and Action Plans establish a collaborative, partnership-based approach to enhance and promote water stewardship in the NWT at all levels. The Action Plans have Keys to Success that are organized under the four components of the Water Strategy: Work Together, Know and Plan, Use Responsibly, and Check Our Progress. Each Key to Success has a set of Action Items that include lead and supporting water partners and deliverable dates. Under the Check Our Progress component, lead and supporting water partners have committed to reporting their progress in a variety of ways including annual surveys, participation in the annual Water Strategy Implementation Workshops, and participation in the annual progress review.

The 2016-2020 and 2021-2025 Action Plans identified performance indicators to track the effectiveness of implementation. The 2016-2020 Action Plan included 147 Action Items and 54 Performance Indicators to measure Water Strategy implementation progress. The performance indicators are tracked annually and reported in the annual progress review summary report and comprehensive spreadsheet.

Independent evaluations of the Water Strategy are also undertaken every five years to determine progress and address challenges by outlining recommendations for subsequent Action Plans. An independent evaluation of the 2016-2020 Action Plan (Ref. 5) was completed in September 2020 and informed the development of the five-year Action Plan for 2021-2025.

This indicator was prepared by the Government of the Northwest Territories, Department of Environment and Climate Change using internal information.

NWT Focus

The purpose of the Water Strategy is to proactively care for our water on a territory-wide basis, and to take the steps necessary today to achieve the vision of the Water Strategy: “The waters of the Northwest Territories will remain clean, abundant and productive for all time.”

Through the Action Plan, the creation of Action Items and Performance Indicators makes it possible to track progress and identify and address gaps.

Current View: status and trend

The 2019/2020 NWT Water Stewardship Strategy Progress Review was the fourth and final annual progress review of the second Action Plan, which came to a close at the end of 2020 (Ref. 6). The progress review was prepared based on survey responses from water partners, communications with lead water partners, document review and database analytics. The graphic below summarizes progress towards completing actions in the 2016-2020 Action Plan – overall, 57% of action items were completed, 42% were in progress, and 1% was not started.

Looking around

The NWT Water Stewardship Strategy was developed collaboratively with water partners in the NWT. This partnership approach to strategy development, including guidance by an Indigenous Steering Committee, is one of the features that makes it unique in Canada.

Alberta’s Water for Life strategy, British Columbia’s Living Water Smart strategy and upcoming Watershed Security strategy, and Yukon’s Water for Nature, Water for People strategy, are examples of other water strategies in the Mackenzie River Basin.

Looking forward

The Department of Environment and Climate Change is working collaboratively with water partners to implement the 2021-2025 five-year Action Plan for the Water Strategy focusing on key priority areas:

- ensuring Indigenous knowledge, perspectives and values guide Water Strategy activities;

- improving communication to build public awareness;

- promoting and supporting community capacity building through community-based monitoring programs, including Guardian programs;

- engaging youth in water stewardship in the NWT;

- continuing transboundary water agreement negotiations and implementation; and,

- increasing our understanding of aquatic ecosystem health, including groundwater, in the NWT.

Find out more

For more information about the Water Strategy, as well as related documents and resources, please visit http://waterstewardship.ca.

References

Ref. 1. GNWT. 2018. Northern Voices, Northern Waters: NWT Water Stewardship Strategy. Available at: https://www.ecc.gov.nt.ca/sites/ecc/files/resources/nwt_water_stewartship_strategy_web.pdf

Ref. 2. GNWT. 2011. NWT Water Stewardship: A Plan for Action 2011-2015. Available at: https://www.nwtwaterstewardship.ca/sites/water/files/resources/nwt_water_strategy_action_plan.pdf

Ref. 3. GNWT. 2016. Northwest Territories Water Stewardship Action Plan 2016-2020. Available at: https://www.nwtwaterstewardship.ca/sites/water/files/resources/nwt_water_stewardship_strategy_plan_for_action_2016-2020.pdf

Ref. 4. GNWT. 2021. Northwest Territories Water Stewardship Action Plan 2021-2025. Available at:

https://www.nwtwaterstewardship.ca/sites/water/files/resources/wss_actio...

Ref. 5. GNWT. 2020. Evaluation of the NWT Water Stewardship Strategy Action Plan 2016-2020. Available at:

https://www.nwtwaterstewardship.ca/sites/water/files/resources/publicati...

Ref. 6. GNWT. 2020. 2019/2020 NWT Water Stewardship Strategy Progress Review. Available at: https://www.ecc.gov.nt.ca/sites/ecc/files/resources/wss-web_high_res.pdf

17.3. Status of planning and implementation of species at risk recovery actions

This indicator provides information on the status of management and recovery planning actions for NWT species assessed as “at risk” in the NWT (Ref. 1) and Canada (Ref. 2).

In the NWT, the Species at Risk (NWT) Act came into force in February 2010. The Act and associated regulations support collaborative processes to identify, protect and facilitate the recovery of species at risk in the Northwest Territories (NWT). Across Canada, the Species at Risk Act (2002) provides for the recovery and conservation of species at risk in Canada. These two pieces of legislation are designed to work together to protect species at risk and their habitats across their distribution in the NWT and Canada.

This indicator tracks the assessment, listing and recovery actions for species at risk in the NWT and Canada under both territorial and federal legislation,

Species at risk processes and legislated timelines for the NWT and Canada

Key Processes

Key Processes

Assessment à Listing à Planning à Implementation à Progress Reporting

Northwest Territories

Species at Risk (NWT) Act

- Assessment à Listing: 12 months from assessment to consensus agreement + 3 months to legal listing

- Listing à Planning: 2 years to develop a Management Plan or Recovery Strategy for Special Concern or Threatened species; 1 year to develop a Recovery Strategy for Endangered species from listing

- Planning à Implementation: 9 months to consensus agreement on implementation

- Implementation à Progress Reporting: 5 years from implementation agreement to progress reporting

Canada-wide

Species at Risk Act

- Assessment à Listing: 9 months to legal listing

- Listing à Planning: 3 years for Special Concern, 2 years for Threatened, 1 year for Endangered

Planning à Progress Reporting: 5 years from publication of recovery strategy/management plan to progress reporting

Information on the status of assessment, listing and recovery management actions are tracked and reported by the Conference of Management Authorities (CMA) in the Northwest Territories and by the Government of Canada for activities across Canada.

This indicator was prepared by the Government of the Northwest Territories, Department of Environment and Climate Change using information provided by all wildlife management authorities in the NWT.

NWT Focus

Some species in the NWT are facing threats due to human activities or natural processes, and other species are simply very rare. The loss of a single species can have negative consequences that can ripple through an ecosystem.

In the NWT, the responsibility for the conservation of biodiversity is shared by organizations that share management responsibility for species at risk in the NWT, including the federal, territorial and Tłı̨chǫ governments, and wildlife co-management boards established under settled land claim agreements. The status of species at risk recovery planning and actions provides an overview of our combined efforts to support species recovery and management actions protect, conserve and recover species at risk in the NWT.

Current View: status and trend

Northwest Territories processes

A total of 21 species in the Northwest Territories have been assessed under the Species at Risk (NWT) Act, resulting in 12 legally listed species (as of July 2021) (Table 1; Ref. 1). Five species were found to be data deficient—that is, there was not enough information to determine their status. Three species were assessed as Not at Risk in the NWT, and one species was assessed as Special Concern but not listed. Ten of the 12 listed species have recovery strategies or management plans in place, as well as agreements to implement these actions.

Table 1: Species legally listed under the Species at Risk (NWT) Act. Activity implementation tracking: blue (completed), yellow (delayed), green (on track). Source: Ref. 1. Updated to July 2021

The Species at Risk (NWT) Act requires formal progress reporting every five years. In the NWT, the CMA is required to report publicly on the actions undertaken to implement a management plan or recovery strategy and progress towards meeting its objectives. The first formal report was published in 2021 for Hairy braya (Table 2).

Species at Risk (NWT) Act Progress Reporting

Table 2: NWT progress reporting timelines

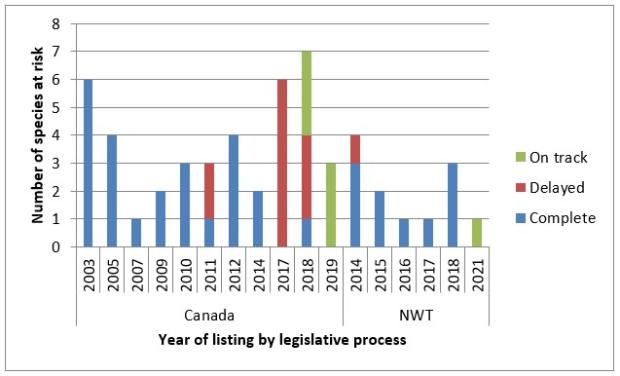

Canada-wide processes

A total of 47 species occurring in the NWT are currently assessed as being at risk under the federal Species at Risk Act, resulting in 41 legally listed species with 8 more species under consideration for listing (as of April 2021) (Ref. 2.). Twenty-four of these species currently have recovery strategies or management plans in place.

The federal Species at Risk Act requires progress reporting on recovery strategies and management plans every five years until their objectives have been achieved. To date, progress reporting has been completed for three species occurring in the NWT (boreal caribou , grey whale, and northern wolffish).

Table 3: Canada-wide species at risk and progress on recovery actions. Activity implementation tracking: Blue (completed), yellow (delayed), green (on track).

Looking around

Most jurisdictions in Canada have signed the national Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk and, in doing so have agreed to work towards a national approach for protecting species at risk. The overall goal of these efforts is to prevent species in Canada from becoming extinct as a consequence of human activity.

The NWT is one of eight Canadian jurisdictions with its own species at risk legislation. The NWT process is unique in that it uses a consensus-based approach for the assessment, listing then management and recovery of species at risk. Together, the wildlife co-management boards and governments that share responsibility for the conservation and recovery of species at risk in the NWT (Conference of Management Authorities) provide direction, coordination and leadership on species at risk while respecting the roles and responsibilities of individual Management Authorities under legislation, land claims and self-government agreements.

The extent and status of recovery planning in other provinces and territories is influenced by how long legislation and species at risk programs have been in place, as well as the number of species and threats. For example, in Ontario, where the province’s Endangered Species Act (ESA) has been in place since 1971 and there are many species impacted by human activities, a total of 245 species at risk have been listed as of March 2021 (Ref. 2, 3).

Looking forward

Success in the conservation and recovery of species at risk relies on the commitment and cooperation of all management authorities and other wildlife co-management partners who are involved in implementing the approaches and actions set out in management plans and recovery strategies. All northerners are encouraged to advocate for and support implementation of these plans, as a way to benefit the recovery of species at risk, support biodiversity in the NWT, and sustain the land-based way of life enjoyed by northerners, and in particular Indigenous peoples.

NWT species at risk legislation is just over a decade old. As more species are assessed, listed and re-assessed, recovery planning and implementation will continue to advance. It is important that we continue to evaluate our progress as we go, so we can learn and adjust our approaches to conservation and recovery to ensure they are effectively protecting our species at risk in the NWT.

Find out more

Supporting documents, including management plans and recovery strategies, are published on the NWT Species at Risk website and the national Species at Risk Public Registry. Information on the biological status of NWT species at risk is available from the NWT Species at Risk Committee (SARC) or the Committee on the Status of Endangered Species in Canada (COSEWIC).

- Discover all recovery projects funded under the Species Conservation and Recovery Fund (SARF) in the NWT here: https://nwtgeomatics.maps.arcgis.com/apps/Shortlist/index.html?appid=207ba65373734e7e82ce7daab7b25b39

- Species at Risk (NWT) Act available at https://www.justice.gov.nt.ca/en/files/legislation/species-at-risk/species-at-risk.a.pdf

- Species at Risk Act (Canada) available at https://laws.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/S-15.3/

- For more information on species at risk in the NWT go to https://www.nwtspeciesatrisk.ca/

- For more information on the Conference of Management Authorities (CMA) go to https://www.nwtspeciesatrisk.ca/CMA

- For more information on the NWT Species at Risk Committee (SARC) go to https://www.nwtspeciesatrisk.ca/SARC

- For more information on the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) go to https://www.cosewic.ca/index.php/en-ca/

- For more information about the Accord on species at risk in Canada go to https://www.registrelep-sararegistry.gc.ca/6B319869-9388-44D1-A8A4-33A2F01CEF10/Accord-eng.pdf

Technical Notes

Species at risk are assessed and listed in one of five status categories:

Extinct: a species that no longer exists anywhere in the world.

Extirpated: a species that no longer exists in the wild in a particular region (Canada or NWT) but exists elsewhere.

Endangered: a species that is facing imminent extirpation or extinction.

Threatened: a species likely to become an endangered species if nothing is done to reverse the factors leading to its extirpation or extinction.

Special Concern: a species that may become threatened or endangered because of a combination of biological characteristics and identified threats.

Not at risk: species was assessed and found to be not at risk of extinction given the current circumstances.

Data deficient: species was assessed but there was not enough information to determine the status.

References

Ref. 1. NWT Species at risk. 2021. Species at risk at a glance. Available at https://www.nwtspeciesatrisk.ca/SpeciesAtRisk

Ref. 2. Government of Canada. 2021. Species at risk public registry. Available at https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/species-risk-public-registry.html.

Ref. 3. Bergman J., Binley A., Murphy R., Proctor C., Nguyen T., Urness E., Vala M., Vincent J., Fahrig L., and Bennett J. 2020. How to rescue Ontario’s Endangered Species Act: a biologist’s perspective. Facets, 5(1): 423-431.

Ref. 4. Olive A, and Penton G. 2018. Species at risk in Ontario: an examination of environmental non-governmental organizations. The Canadian Geographer/Le Géographe canadien, 62(4): 562-574.

17.4. Status of implementation of the NWT Climate Change Strategic Framework

The 2030 NWT Climate Change Strategic Framework (CCSF) (Ref. 1) sets out the Government of Northwest Territories’ (GNWT) long-term plan for addressing climate change in the NWT. Following public engagement in 2016 and 2017, the CCSF was published in May 2018. The CCSF outlines territorial plans to respond to challenges and opportunities associated with a changing climate, moving towards an economy that is less dependent on fossil fuels, improving climate change knowledge, and building resilience and adapting to climate change, while contributing to national and international efforts to address climate change.

The 2030 NWT Climate Change Strategic Framework 2019-2023 Action Plan (Action Plan) (Ref. 2) was published in April 2019 and guides the first five years of implementation of the CCSF. The Action Plan presents priority actions led mainly by the territorial government, along with federal, Indigenous and community governments, and non-governmental organizations. The Action Plan includes the implementation of the 2030 Energy Strategy (Ref. 3), which is specifically focused on climate change mitigation actions, and the implementation of the NWT Carbon Tax (Ref. 4), that encourages carbon conservation and substitution to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The Action Plan also outlines important areas for future collaboration, where the identified actions will require significant federal investment and funding to move forward, in addition to new funding and/or support from the GNWT, academia, non-government organizations, industry, and other funding agencies.

The GNWT reports on the implementation of the CCSF Action Plan in an annual report (Ref. 5). Climate change reporting is aligned and integrated with Energy Strategy (Ref. 6) and Carbon Tax (Ref. 7) reporting by integrating the three reports into an annual Plain Language Overview Report released in the fall (Ref. 8).

This indicator was prepared by the Government of the Northwest Territories, Department of Environment and Climate Change using internal information.

NWT Focus

Under the Paris Agreement, Canada is committed to a 30% reduction in annual emissions from 2005 levels by 2030. To implement this commitment, the federal government, provinces and territories worked together to develop the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change released in December 2016 (Ref. 9). As a signatory to the Pan-Canadian Framework, the GNWT built upon these efforts to address climate change within our territory, through the implementation of the CCSF, the 2030 Energy Strategy, and accompanying action plans.

It is necessary to report on the implementation of the CCSF to assess the territory’s progress on transitioning to a lower carbon economy, improving knowledge on climate change impacts, and building resilience and adapting to a changing climate, in the Canadian context. Knowledge on climate change in the NWT – both western science and traditional knowledge based – is critical to assessing the state of our environment. Further, tracking how we are responding to climate change impacts can indicate whether we are prepared to adapt to probable environmental and ecosystem change.

Current View: status and trend

The second year of reporting on the Action Plan was April 1, 2020 to March 31, 2021 (Ref. 5). The Action Plan is divided into two parts. Part 1 is work that was already underway or will be initiated and resourced in the 2019-2023 timeframe. There are a total of 104 action items under Part 1. In 2020-2021, 72 of these actions were on track, 31 were complete and one not yet initiated. All action items are anticipated to be complete by March 31, 2023 (Figure 1).

The action items are organized under the following goals and cross-cutting themes:

- Goal #1 - Transition to a lower carbon economy

- Goal #2 – Improve knowledge of the climate change impacts.

- Goal #3 – Build resilience and adapt to a changing climate.

- Cross-Cutting Themes – Leadership, communication and capacity and economic impacts and opportunities

Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) report that NWT emissions in 2020 have decreased by 19% [1] relative to 2005 emissions (Ref. 10) demonstrating progress on Goal #1. GHG emissions from the NWT represent 0.2 % of Canada’s emissions (Ref 10). In the NWT, there are significant technical challenges and high cost to reducing emissions (e.g. in the high Arctic there are less substitution options).

Part 2 identifies high priority action areas that require funding and/or additional capacity to proceed. Of the 57 tasks identified in Part 2, 23 were designated as initiated in 2020/21, two were completed, and three were not yet initiated. However, many action areas under Part 2 are not fully resourced and require additional funding or staff to achieve their intended outcomes.

The GNWT is actively seeking funding from the federal government, as well as exploring opportunities for third-party funding, to resource Part 2 action areas.

Looking around

Federal, provincial and territorial governments report on climate action progress through the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change. Approaches and scope of work vary by jurisdiction, with some having specific climate change action plans while others incorporate climate action into government wide planning and reporting. The Pan-Canadian Framework’s annual synthesis reports summarize climate action across Canada at a high-level.

Looking forward

The GNWT will continue to provide annual progress reports until 2023-2024. In 2024, an evaluation and formal review of the CCSF and Action Plan will be conducted to inform potential revisions to the CCSF and the development of the 2025-2029 Action Plan.

Find out more

To find out more about the GNWT’s integrated approach to climate change go to: https://www.ecc.gov.nt.ca/en/services/climate-change/integrated-approach

Due to the far-reaching impacts of climate change, there are many additional indicators in this State of the Environment report that have trends impacted by climate change:

- Indicator 1.2 - Trends in global environmental changes

- Indicator 1.3 - Trends in global CO2 concentrations

- Indicator 1.4 - Trends in global oscillations such as El Nino

- Indicator 2.1 - Trends in observed seasonal weather compared to normal

- Indicator 2.2 - Trends in lightning events

- Indicator 2.3 - Projected trends in temperatures and precipitation in the Arctic

- Indicator 9.1 - Trends in temperatures in the Beaufort Sea

- Indicator 9.2 - Trends in ocean acidification

- Indicator 9.3 - Trends in projected sea rise levels in Beaufort Sea

- Indicator 9.4 - Trends in Arctic sea ice

References

Ref. 1. GNWT. 2018. 2030 NWT Climate Change Strategic Framework. Available at: https://www.ecc.gov.nt.ca/sites/ecc/files/resources/128-climate_change_strategic_framework_web.pdf

Ref. 2. GNWT. 2019. 2030 NWT Climate Change Strategic Framework 2019-2023 Action Plan. Available at: https://www.ecc.gov.nt.ca/sites/ecc/files/resources/128-climate_change_ap_proof.pdf

Ref. 3. GNWT. 2017. 2030 Energy Strategy. Available at: https://www.inf.gov.nt.ca/sites/inf/files/resources/gnwt_inf_7272_energy_strategy_web-eng.pdf

Ref. 4. GNWT. 2019. Petroleum Products and Carbon Tax Act. Available at: https://www.fin.gov.nt.ca/en/services/carbon-tax

Ref. 5. GNWT. 2020. NWT Climate Change Action Plan Annual Report 2020-2021. Available at: https://www.ecc.gov.nt.ca/sites/ecc/files/resources/climate_change_report_-_2021_-_final-web_0.pdf

Ref. 6. GNWT. 2020. Energy Initiatives Report 2019-2020. Available at: https://www.inf.gov.nt.ca/sites/inf/files/resources/3758_-_gnwt_exec_-_energy_initiatives_report_final-dec17-web-hires.pdf

Ref. 7. GNWT. 2020. NWT Carbon Tax Report 2019-2020. Available at: https://www.fin.gov.nt.ca/sites/fin/files/resources/gnwt_carbon_tax_report_2019-2020_web.pdf

Ref. 8. GNWT. 2020. Responding to Climate Change in the NWT Plain Language Overview Report 2019-2020. Available at: https://www.ecc.gov.nt.ca/sites/ecc/files/resources/responding_to_climate_change_in_the_nwt_-_overview_2019-20.pdf

Ref. 9. Government of Canada. 2016. Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change. Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/services/environment/weather/climatechange/pan-canadian-framework.html

Ref 10. Environment and Climate Change Canada. 2022. National Inventory Report 1990-2020: Greenhouse Gas Sources and Sinks in Canada. Park 3. Canada’s Submission to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. ISSN: 1910-7064. Available At.

https://unfccc.int/documents/461919

[1] Note. NWT GHG yearly emission and reduction estimates prepared by ECCC are subject to change and should interpreted as having uncertainty. Both 2005 and 2020 estimates and resulting percentage change in emissions relative to 2005 will change in future National Inventory Reports as GHG estimation methodologies are refined.